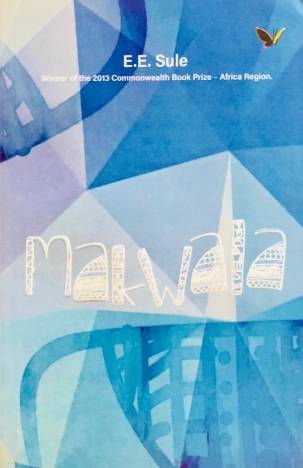

Book: Makwala

Author: E. E. Sule

Publisher: Origami

Year of Publication: 2018

Reviewer: Bizuum Yadok

Have you ever felt like throwing up while while reading a book and still be spellbound by the same book? It clearly explains why a number of people whom I have sought their opinion about the Makwala were hesitant in giving me an oral review. Most times they just stop at “it’s an interesting book.”

The book is actually hard to describe in a single breath being that it hovers between individual and communal relationships simultaneously, as such it is fitting that the book is titled after the community that hosts a large chunk of its setting.

The absence of a singular protagonist or villain, is perhaps one of the achievements of the book, except if, perhaps, Makwala is treated as a person. However, two friends, Ende and Jackson bear the weight of most of the story. Whatever is left is shared among Odula, Martha, Mama Maria and other visible characters of the Makwala community. Within the relatively short plotline of the story, drastic changes occur in and with the settlement and as expressed at the tail end of the story by Mama Maria a.k.a Mama Makwala in Pidgin:

“Hmmm. My Makwala don change. Even you Baba Ende don change. . .” (P. 322).

Any reader of the text from its beginning to the end would admit that all the prominent characters in the fictitious slum of Makwala are dynamic. Jackson, for example, grows from an innocent teenagehood – having been raped anally on different occasions – into a weed smoker and a serial killer. Ende, Jackson’s erstwhile best friend, suffers from bouts of insanity and finally decides to walk away from his father. Quite ironically, their female peers, Kemi and Nelly, trudged on the path of a more positive acceptable behavior. It appears that most of the children in Makwala are products of dysfunctional families and the decaying atmosphere of the neighborhood further complicates their (under)developmental trajectory. Jackson is the son of a prostitute, Ende is the son of a runaway father who impregnates a mad woman and is forced to raise the boy as a single father. Nelly is a daughter of a prostitute and Kemi happens to share siblings from multiple fathers. Jackson is deprived of a father figure while Ende endlessly seeks maternal love. The two boys happen to retain vestiges of their parents’ behavior. Jackson manifests the killer instincts of his assassin of a father while Ende, despite his coordinated mien, exhibits flashes of insanity perhaps inherited from his mother.

Makwala, still, offers a kaleidoscopic view of a society united in debauchery and poverty. It is hard to imagine that Makwala is housed by the the conservative Kano State of Nigeria, where religious police (Hisbah – or Habsih in the text) have more powers than the police to maintain law and order especially at the dawn of the 4th republic when the controversial matter of Shari’a Law was striving to have its tentacles on all people of Nigeria’s north. However, Makwala has its semblances in the backyards of almost all cities of Nigeria, where a number of its inhabitants venture into the heart of the cities to labour and return at dusk to wallow in their frustration. Odula, Simon, and Ogoja Boy represent this crop in Makwala. Consumption of hot drinks and smoking of marijuana become their means of escape from the dark reality that confronts them.

Martha, Jackson’s mother, has seen it all in the trade and art of prostitution but she refuses to give it up even for the sake of her son. This eventually becomes her undoing. She is just one of the numerous prostitutes portrayed in E.E. Sule’s Makwala. There is the pit which is the cauldron of vices in the novel, including sexual orgy. Similar to prostitution, and also glaring in the book, is the matter of homosexuality gleaned from Nasir, Ado, Yohanna, the Senator and others with Jackson as an object of abuse and coercion into sodomy. It is likely that the name Jackson is an allusion to the globally acclaimed talented American singer and entertainer, Michael Jackson, whose fame robbed him of an innocent childhood and launched him into drug abuse and identity crisis. Jackson is talented as a visual artist and is undeniably handsome but handsomeness lands him in more trouble than fortune.

Makwala joins a stream of contemporary novels like Elnathan John’s Born on a Tuesday and Abubakar Adam’s Season of Crimson Blossoms to provide evidence of homosexuality as part of urban reality whether as a borrowed culture or, arguably, as a natural phenomenon. This kind of content, along with poverty porn, squalor, religious hypocrisy, and corruption, feeds into Western stereotypes of the Nigerian situation. Thus, it guarantees speed in the distribution and sales of the product.

The book presents an omniscient narrator but the first person appears sparingly, culminating in a distinct style of the author. The suspense also captivates the reader and keeps him guessing how it will end even though the book ends on a hopeful note. The language is most times poetic which doesn’t betray the author’s talent as a poet. The book admits a generous mixture of pidgin and some sprinkling of Hausa in the dialogues therein, reflecting mode of communication in a slum which serves as a microcosm of Nigeria. Some aspects of the narrative appear incredible and contributes little or nothing to the storyline save for the author’s desire to forcefully invite a theme to the text. Odula’s trip to his hometown in the event of communal clash is a case in point.

On the whole, the novel presents a putrefying society, Makwala, sandwiched by the conservativeness and futile moral policing of Kano. It is the commoner’s story but even the commoner has a stake in turning the tides of a city or even a nation. It is a book that deserves another reading but I am not sure if I can stomach the irritating vignettes of the story.